Taming the Wandering Mind: Training Your Attention with Mindfulness Meditation

In the chaotic rush of modern life, finding a moment of calm can seem unattainable. Perhaps you’ve considered meditation but felt overwhelmed by the idea of sitting still or quieting your racing thoughts. If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Many individuals struggle with initial attempts at mindfulness meditation, often feeling frustrated or uncertain about how to approach the practice. To begin, it’s crucial to dispel two common misconceptions:

1. Relaxation Isn’t the Ultimate Goal:

While relaxation can be a byproduct of meditation, it’s not the primary objective. Mindfulness meditation is about embracing every aspect of the present moment, whether pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. It’s learning to face life’s challenges with less reactivity and more ease, fostering resilience in the face of difficulties.

2. It’s Not About Controlling Your Thoughts:

Instead of suppressing or eliminating thoughts, mindfulness acknowledges the mind’s tendency to wander. By observing these wandering thoughts without judgment, we gain insight and learn to relate to our mental processes more skillfully.

So, how do you embark on this mindfulness journey?

A great starting point is breath awareness meditation. This practice uses the breath as an anchor, a stable point to return to whenever the mind drifts away, as it inevitably will. Think of it like training a puppy: gently guiding your attention back to the breath, just as you would encourage a puppy to stay put. It’s not about scolding yourself when your mind wanders; instead, it’s about the patience and gentle redirection of your focus.

With consistent practice, you’ll notice your mind gradually calming, concentration strengthening, and an increased ability to open your attention to various aspects of your experience. From bodily sensations to thoughts, emotions, and the ever-changing flow of your consciousness, mindfulness expands your awareness profoundly.

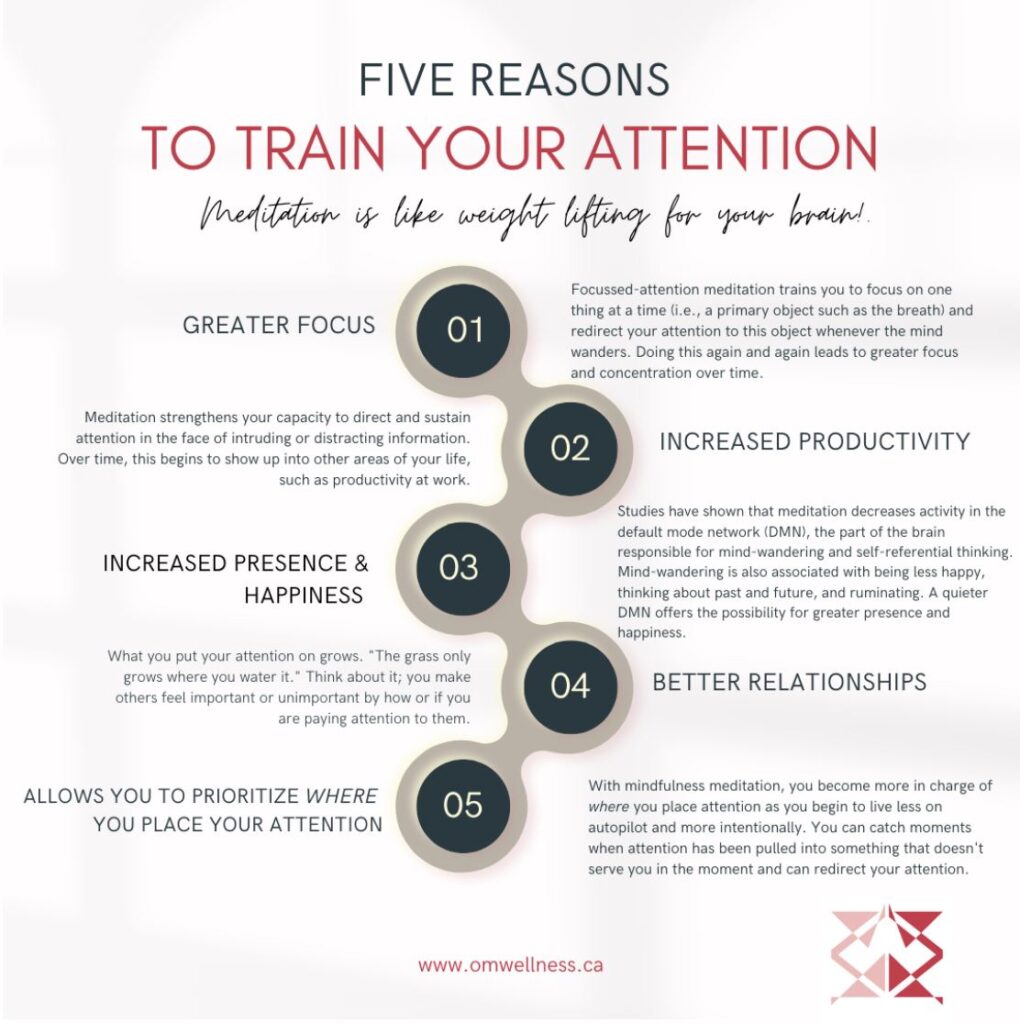

The Benefits of Training Your Attention

The Benefits of Training Your Attention

The advantages of breath awareness practice extend far beyond the cushion. You enhance your productivity and efficiency by cultivating focused attention, especially when distractions abound. As the saying goes:

“Where your attention goes, your time goes” – Idowu Koyenikan

Moreover, a wandering mind often leads to living on autopilot, where you’re physically present but mentally absent. The more mindful you become, the more you gain command over your attention and, consequently, your choices in life. This heightened awareness also significantly impacts relationships; what we focus on tends to flourish.

Mindfulness Meditation: Your Mental Gym

Consider breath awareness meditation as weightlifting for your brain. Each session flexes your mindfulness muscle, enhancing your ability to focus and offering relief from the mind’s constant chatter. The more you practice, the more substantial the benefits, transforming your attention and overall well-being.

Ready to begin your mindfulness journey? Explore this 15-minute Breath Awareness and embark on the path to a calmer, more focused mind: https://insighttimer.com/jen/guided-meditations/15-minute-awareness-of-breath

And for a quick reference of the reasons to train your attention, see the diagram below. Not sure how to get started? Sign up for an introductory class or a mindfulness-based stress reduction program – considered the gold standard in modern mindfulness training, or have a look at our corporate programs.